Are we beating cancer? Or is cancer beating us?

Cancer has become one of the most common causes of death globally. Current estimates show that 1 in 5 people will develop cancer in their lifetime. An estimation that has risen by 36% over the past decade. The World Health Organization predicts that by 2050, there will be over 35 million new cancer cases, representing a 77% increase compared to today. Making one thing clear: the global cancer burden is increasing.

But why is this happening? And what about the available treatments? Are they failing?

In reality, the rising cancer burden is driven by several key factors:

👴 Ageing populations: Cancer risk increases significantly with age (especially after 60 years), and people are living longer worldwide.

🩺 Better diagnostics: Improvements in screening tools/tests and medical imaging mean more cancers are being detected.

🧬 Lifestyle and environmental factors: pollution, diet, and sedentary lifestyle, among other factors, can contribute to the rising incidence of certain cancer types.

So, to answer the question: no, available treatments are not failing. In fact, cancer therapies have improved and helped to significantly increase the survival rates (for certain cancer types).

Thanks to research on carcinogenesis mechanisms and genetic mutations, more treatment options besides chemo/radiotherapy and surgery are available. Some of these latest approaches are: ADCs (Antibody Drug Conjugates), gene therapy, stem cell therapy, immunotherapy, nanoparticles, and photodynamic/photochemotherapy.

For instance, in immunotherapy, immune checkpoint inhibitors work by targeting specific checkpoint proteins, such as PD-1, PD-L1, and CTLA-4, acting as an off switch to help T cells recognise and attack cancer cells.

However, not all cancers respond equally well to existing therapies. Successful cancer treatment depends on many factors, including the type of cancer. For instance, cancers of the Brain and Central Nervous System (CNS) are difficult to treat, representing a therapeutic challenge. Recent approaches have been using genetically engineered viruses (Oncolytic virotherapy), as is the case with using Oncolytic Zika Virus (ZIKV). ZIKV selectively infects and induces cell death (apoptosis) in GSCs (Glioblastoma Stem Cells) by triggering a pro-inflammatory response and promoting the activation and infiltration of T-cells within the tumour. Currently, this promising approach is at the pre-clinical phase, as further investigations are needed.

Despite the progress in oncology, there is still a need for further innovative therapeutic solutions. Common limitations among the current therapeutic approaches are:

📌 Surgery can be restricted by tumour size, location and metastasis.

📌 Tumours can easily suppress the immune environment.

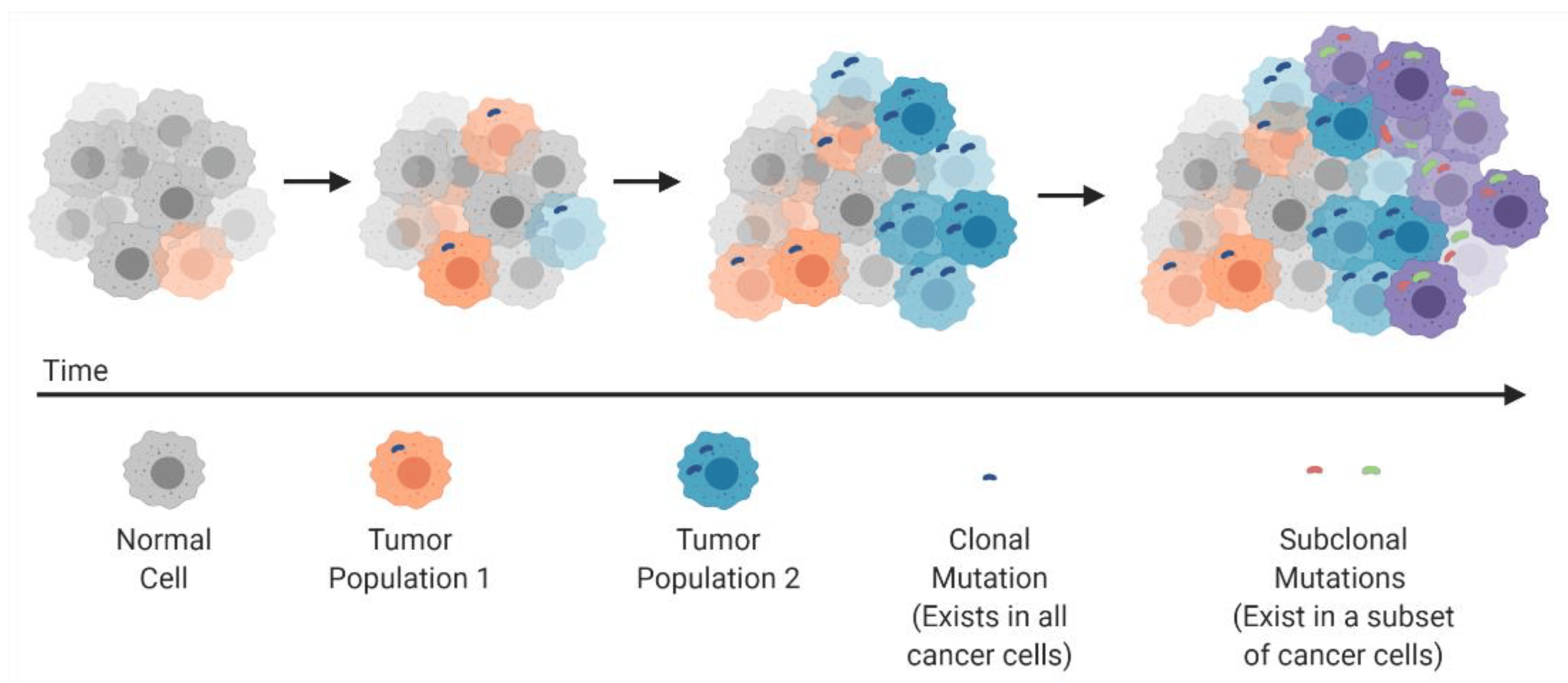

📌 Tumour heterogeneity and cancer stem cells (CSCs) can drive resistance to therapy.

Clonal evolution and development of tumor heterogeneity: cancers arise through stepwise, somatic cellular mutations inevitably leading to multiple sub-clonal populations. Source: "Tumor heterogeneity: a great barrier in the age of cancer immunotherapy." Cancers 13.4 (2021): 806. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13040806

Dr Arseniy Yuzhalin, in his article “Redefining cancer research for therapeutic breakthrough”, argues that future progress in effective treatments depends on embracing the complexity of tumours: their molecular interactions and evolution with the microenvironment. Such approach in cancer research is evident in single-cell sequencing studies, which offer insights into the clonal evolution and intratumoral heterogeneity of both primary and metastatic tumours.

This is why research is critical. Through sustained research efforts and collaboration across disciplines, there is hope in overcoming these challenging conditions. Several recent breakthroughs are directly addressing these challenges:

💉 Tackling immune suppression with personalised treatments:

In New York, Dr Vinod Balachandran’s team has taken a remarkable step forward. They developed personalised mRNA neoantigen vaccines. These vaccines can activate strong anti-tumour immune responses in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), a cancer difficult to treat due to its resistance to immunotherapy. Researchers sequenced each patient’s tumour to identify unique neoantigens and created individualised mRNA vaccines encoding up to 20 of these targets. In an early clinical trial, half of the patients developed strong immune responses (to neoantigen-specific CD8⁺ T-cell) and those who did experienced longer recurrence-free survival. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-023-06063-y

🧠 Treating aggressive tumours in difficult areas like the Brain:

In Boston at Massachusetts General Cancer Centre, Dr Marcela Maus’s laboratory is working on a new generation of CAR-T cell therapy to target glioblastoma. In a recent study, researchers engineered T cells, called CARv3-TEAM-E T cells, to target both the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR variant III) and wild-type EGFR. These engineered immune cells were delivered to three patients with recurrent glioblastoma through intraventricular infusion. The results? Within days, patients’ scans showed a dramatic shrinkage of the tumours. Although the responses were transient, these findings demonstrate that CARv3-TEAM-E T cells can safely enter the brain and attack solid tumours. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa2314390

🔬 Understanding tumour evolution and heterogeneity:

At The Francis Crick Institute in London, Dr. Charles Swanton leads TRACERx, the world’s largest study tracking how cancer evolves and becomes resistant to therapy. In a recent study, he and his team analysed 1,644 tumour regions from 421 patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and were able to map how lung cancers grow, mutate, and adapt over time. By sequencing these multiple tumour regions, they demonstrated that lung cancers are highly heterogeneous. They reported that some mutations (often in key drivers like TP53) are present everywhere in the tumour from the beginning (truncal mutations), while others appear later (subclonal mutations) and contribute to metastasis, immune evasion, and therapy resistance. Researchers constructed phylogenetic trees for 401 tumours which enabled them to understand when different mutations appeared, how tumour subclones branched off, and which ones became dominant over time. These findings are significant for predicting tumour progression and designing smarter, more effective and adaptive lung cancer treatments.

Supporting translational research in cancer helps:

💡 Develop novel, innovative therapies that can reach and target tumours more effectively in a personalised manner.

🩺 Improve diagnosis, treatments, and survival rates.

💜 Bring hope to patients and families facing limited options.

And you can help us accelerate this progress!

Our campaign, This Is For Me-This Is For Science, has the mission to narrow the bench-to-bedside gap by raising funds that go directly toward innovative, groundbreaking cancer research. But we can only achieve this with your support.

You can do so by joining our fitness challenges or creating your own! 🏃🏽♀️🏋️♂️

And if you are a scientist/researcher pushing the limits to improve cancer outcomes, your team/group can be among our funding awardees 🧫💊. Visit our website to learn more.

Relay for Research at Surrey Research Park in support of This is For Me - This is For Science

Any miles count. Let’s beat cancer.